Do people really prefer traditional architecture?

As Donald Trump's championing of classical architecture resurfaces the traditional-versus-modernist style debate, Lizzie Crook explores what the public wants from the way buildings look.

The US president is on a mission to make federal architecture "Great Again", passing orders prioritising classical and traditional styles for civic buildings, commencing work on an ostentatious new ballroom for the White House and unveiling plans for a triumphal arch in Washington DC.

His campaign has horrified much of America's architecture community, but Trump's supporters argue that the public simply prefers this type of architecture.

Indeed, a 2020 survey commissioned by classical-architecture advocacy group the National Art Society indicated that Americans overwhelmingly favour traditional federal buildings, regardless of background or political inclination.

Other similar surveys – including one commissioned by traditional-focused British studio Adam Architecture in 2009 and another by right-leaning UK think tank Policy Exchange in 2021 – have echoed these findings.

There's even a study to suggest preferences for traditional architecture are evident from infancy.

Nevertheless, British architectural designer Ben Pentreath, known for Georgian-style buildings and dubbed "King Charles's favourite architect" by The Times, is sceptical.

"I get a bit suspicious about popularity contests in architecture and design," he told Dezeen.

"If you wanted to construct an argument through opinion polls which took it in a slightly different direction, I should imagine it would be perfectly possible to do that."

"I think that the debate is very nuanced, and I think that what people are asking for is carefully designed places which work really well."

"Nothing to do with style"

This chimes with the view of Abigail Scott Paul, global head of the Humanise campaign launched in 2023 by British designer Thomas Heatherwick to tackle what he sees as an epidemic of "boring" buildings.

"I think the debate often gets hijacked by quite ideological viewpoints," Scott Paul said.

"What our research shows is it's not about the public preferring traditional styles of architecture over modern styles of architecture, it's whether they're interesting styles or dull styles."

Author and critic Sarah Williams Goldhagen is also opposed to "boring" architecture. The former Harvard professor and specialist in cognitive science and architecture highlighted studies that suggest such buildings can actually increase stress levels.

"By boring, think of undifferentiated glass facades, sort of egg-crate, gridded kinds of buildings with bad detailing and so on," said Goldhagen.

While to many people this might sound like a description of a modernist building, Goldhagen insists the problem is not a question of style.

"It really has nothing to do with style, per se," she said.

"What it does have to do with is the kinds of things that humans routinely scan for in their environments that help them to feel situated in those places that a lot of bad modernist architecture doesn't have."

People are innately drawn to specific details on buildings, such as elements of ornamentation that give a sense of scale, natural light, and tactility, explained Goldhagen.

Older buildings typically have more of these details, which may help explain why they tend to be more popular with the public.

But, she argues, "it's not modernism that's the problem".

"There are plenty of modern architects, like Alvar Aalto and Louis Kahn – you could go on and on – who understood these things about materials and light and detailing and put them in their architecture, and everybody loves them."

Humanise studies gathering the views of people living in England's post-war New Towns and in Seoul both found interest in characterful modern architecture.

"There's a global picture that people are dissatisfied with the bog standard, kind of lazy, fast architecture that's been going up and want something different," said Scott Paul.

"The research demonstrates that people are after buildings that have character in some shape and form, and that can be buildings that demonstrate distinctiveness or character from a long time ago – more traditional forms of architecture – but also modern buildings."

Pentreath agrees that anti-modernist architectural sentiment is at least partly fuelled by frustrations about the poor quality of much contemporary development.

For example, he argues that for a large residential project to be successful, it needs well-designed landscaping, infrastructure, and the provision of basic services.

"Most development that's happened in the last 50 years doesn't deliver any of that stuff," he said.

"They are interested in the facades as well, but what I would say is that people are able to distinguish between good and bad development," he continued. "It's not just about facade design. Definitely not."

Pentreath points to his Roussillon Park housing project in Chichester, which consists of 250 homes that are similar in scale to nearby Georgian, Regency and early Victorian housing but were designed to feel "intentionally contemporary".

"It doesn't have any historical elements at all, it's all quite stripped down," he said. "And it's very popular, a lot of people like that site. People who like traditional housing development are really drawn to that."

"Some buildings have more of a chance"

Like Goldhagen, Glasgow University professor Rebecca Madgin has explored the way that we connect to buildings on a psychological level.

Her work on "personalities of place" suggests there may be other reasons why people form attachments to traditional buildings that go beyond aesthetics altogether.

"My research found that these personalities are influenced by a combination of tangible elements, for example, their architectural style, history, materiality, colour, texture, along with several intangibles," she said.

"Including, how those places are intertwined with our everyday rhythms and routines that generate meanings and memories by narrating the stories of our lives."

Madgin believes anyone can form an attachment to any type of building, "but some buildings have more of a chance than others".

"I don't think this can be simplified to the way that buildings look or the style that they're built in, but rather to think about this alongside the feel and use of the building," Madgin said.

This means that, for example, we are likely to feel more warmly towards a row of houses than to an office block.

Older buildings may also have an inherent advantage in soliciting feelings of fondness for the simple fact they have stood the test of time.

But Scott Paul notes that while many traditional buildings are loved, there are also "very loved modern buildings" such as the Eden Project, by Grimshaw Architects, in Cornwall, south-west England.

"There are modern buildings across the world that people quite quickly form strong attachments to," she said.

Meanwhile, Catherine Croft, director of architecture conservation charity the Twentieth Century Society, points out that our impression of the way buildings look and feel is heavily influenced by how well they are maintained.

This, she argues, is often a challenge facing modern architecture.

"We accept that traditional building materials and components need painting, cleaning and oiling, but very often expect modern ones to be totally resilient and to need no ongoing care, which is unrealistic," she said.

"In many cases a lot of care went into designing surfaces which would age gracefully, and they have done so. In all cases there was a very reasonable assumption, and sometimes specific guidelines, that the building would be regularly maintained and cared for, and the advice hasn't been followed."

Her hope is that as more modernist buildings are successfully restored, their maintenance will be taken more seriously and the public will have a more favourable view of how this type of architecture ages over time.

In any case, Pentreath feels there should be ample space to celebrate all forms of architecture.

"Let's face it, there is a lot of contemporary architecture that is extremely popular," he said.

"It's kind of mad that we collectively are allowing [this subject] to be dressed up as a kind of popularity parade between one style of architecture and another style of architecture."

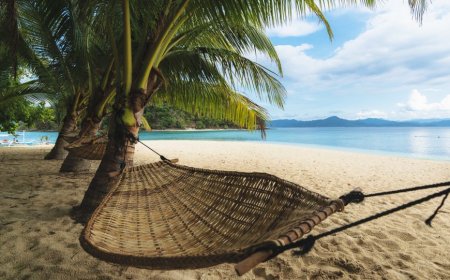

The top photo is by Lily Amateur via Unsplash.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.

The post Do people really prefer traditional architecture? appeared first on Dezeen.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0