an alternative sports bar within the dutch pavilion rethinks togetherness at venice biennale

in our exclusive interview, curator amanda pinatih and designer gabriel fontana delve into the conceptual framework behind SIDELINED. The post an alternative sports bar within the dutch pavilion rethinks togetherness at venice biennale appeared first on designboom | architecture & design magazine.

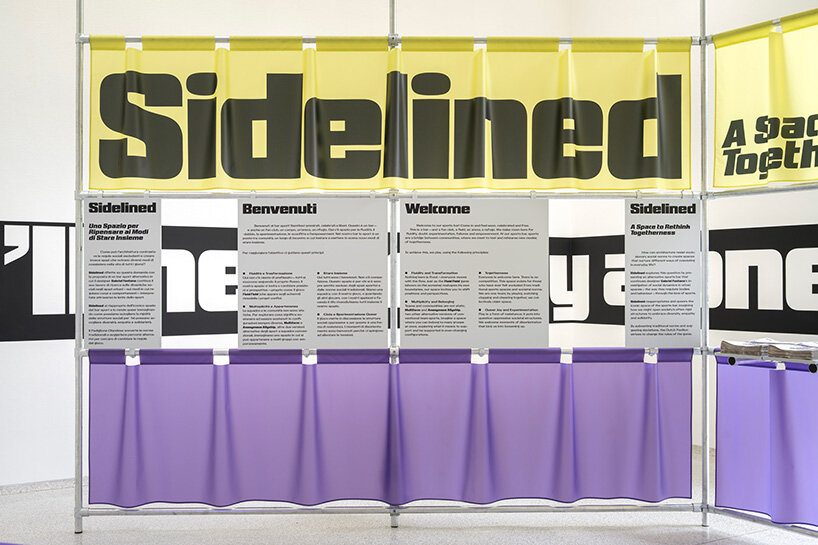

dutch pavilion’s ‘sidelined’ at venice architecture biennale 2025

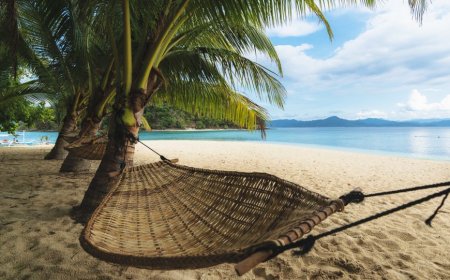

The Dutch Pavilion at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale, commissioned by Nieuwe Instituut, reimagines the typology of national representation as an experimental sports bar. Curated by art historian Amanda Pinatih and driven by the radical sports-based research of designer Gabriel Fontana, SIDELINED: A Space to Rethink Togetherness uses the universal language of sport to challenge social norms and binary thinking. Transformed by artists Koos Breen and Jeannette Slütter into a hexagonal field of fluid interaction, the pavilion becomes a speculative arena, where identity, belonging, and power dynamics are up for play. Fontana’s alternative games, Multiform, Fluid Field, and Anonymous Allyship, reject traditional team structures, uniforms, and rules, turning competition into collaboration.

‘Drawing on Sara Ahmed’s theory of queer phenomenology, we have intentionally queered this space – transforming it into a sports bar that serves as a model for new modes of togetherness,’ Amanda Pinatih tells designboom in an exclusive interview. ‘This is a welcoming space where fluidity and experimentation can lead to a sense of empowerment for visitors. At our sports bar, sports is a tool for bridging diverse communities.’ Players wear shifting jerseys, compete without defined teams, and interact in fields that morph in real time. The goal? Not victory—but connection. ‘By deconstructing the spaces, uniforms, and tools of sport, we can question the conservative values that these elements reproduce and challenge their role in shaping identity,’ explains Gabriel Fontana. ‘Rather than seeing design as merely functional in sports, we will explore how it can be used to radically rethink the values and norms we want to promote on and off the field.’ Amanda Pinatih and Gabriel Fontana explain their approach in depth—keep reading for the full conversation.

all images by Cristiano Corte, unless stated otherwise

queering the rules of play inside a sports bar

Set inside a sports bar filled with queer gym memorabilia, unconventional foosball tables, and screen recordings from Venice’s Stadio Pier Luigi Penzo, the pavilion challenges how we socialize, cheer, and identify with others.

‘We see the sports bar as a place where people can feel welcome or not. As a site of both social production and identity formation, sports bars unite diverse communities around shared experiences, fostering a sense of belonging,’ explains curator Amanda Pinatih. ‘They bridge social gaps by bringing together a wide variety of people, cutting across social, economic, and cultural divides.’ With contributions from artists like Luca Soudant and Alice Wong, the exhibition becomes a living archive of voices, sports bar owners, architects, and community builders, offering a nuanced take on what inclusive design can mean.

Responding to the Biennale’s 2025 theme Intelligens, SIDELINED proposes that architecture isn’t just about buildings—it’s about behavior. ‘Rather than positioning queerness solely as an identity, I treat it as a method—one that challenges norms and creates space for different ways of being, relating, and cooperating,’ designer Gabriel Fontana shares with designboom. ‘These games remove fixed roles and visible groupings, disrupting the standard logics of competition and hierarchy.’ As cheers echo through this queered bar, the Netherlands Pavilion proves that even the most familiar arenas—like sport—can become experimental grounds for empathy, solidarity, and social transformation. Dive into our full interview to hear how architecture meets activism on the field.

the Netherlands Pavilion hosts the electric buzz of a reimagined sports bar | image by Temet.studio

interview with gabriel fontana and amanda pinatih

designboom (DB): What inspired you to frame the pavilion as a queered sports bar, and how does this unconventional setting challenge or expand conventional notions of community and belonging?

Amanda Pinatih (AP): Sport is a universal language. It’s deeply relatable, emotionally charged, and widely accessible. Regardless of your background, most people have some connection to sport, whether through education, participation, fandom, or cultural exposure. This makes it a powerful medium to engage diverse audiences. For the Biennale, Gabriel and I translated his research on sports and society into the field of architecture. While he already treats sport as an architectural system, we felt that the sports bar was an ideal socio-political space for exploring the social dynamics of sport and a great place to watch his alternative team sports Multiform, Fluid Field and Anonymous Allyship.

We see the sports bar as a place where people can feel welcome or not. As a site of both social production and identity formation, sports bars unite diverse communities around shared experiences, fostering a sense of belonging. They bridge social gaps by bringing together a wide variety of people, cutting across social, economic, and cultural divides.

However, this sense of belonging can come at the expense of promoting polarisation. Sports bars can indeed be seen as a microcosm of exclusionary dynamics, reflecting how group identities, rivalry, and opposition can lead to social division. This phenomenon is particularly visible during sporting events, where fans align themselves with specific teams, creating a sense of ‘us vs. them’ that mirrors broader societal polarisations, often encouraging strong in-group loyalty among supporters of the same team while simultaneously promoting out-group opposition to rival fans. By examining how sports bars facilitate interactions among diverse groups—while simultaneously fostering divisions—we can gain insights into the architectural and spatial strategies necessary for creating inclusive public spaces.

curated by Amanda Pinatih and driven by the radical sports-based research of Gabriel Fontana

DB: Your games, Multiform, Anonymous Allyship, and Fluid Field, disrupt the traditional structures of competition. What specific social patterns were you aiming to unlearn or rebuild through these designs?

Gabriel Fontana (GF): Multiform reinvents sports as a form of queer pedagogy by challenging fixed categories and showing us how we can experience the world in a nonbinary way. Transformable uniforms are at the heart of Multiform, disrupting the traditional assumption of a stable team. These uniforms and a three-sided sports field function as tools for disorientation and reorientation, giving players a direct way of experiencing the impact of prevailing norms of identity, community and inclusion. By allowing players to take on fluid identities, Multiform challenges how we conceive of the ‘other’, opening up possibilities for new relations and connections.

Anonymous Allyship explores how belonging influences feelings, behaviour and performance in a group. The goal is to provide a tangible experience of both inclusion and exclusion, revealing the impact of social connection or alienation on individuals and society. In Anonymous Allyship, players come from different generations and communities without traditional visual cues to distinguish their teammates. Everyone wears the same jersey, creating an outside appearance of a single, unified team. However, hidden clues discreetly given players individually create a new dynamic. The first moments of play are filled with uncertainty: To whom do I pass the ball? Who are my teammates? By noticing and remembering how others attack or defend, the players start to understand which team they belong to. From there, patterns start to form.

Fluid Field challenges the binary standards that sporting fields place upon the body: male or female, adult or child, as able-bodied or experiencing limitations. In response, the game takes place on a playing area that is constantly changing shape and dimensions. Projected onto the ground, the pitch shrinks and grows into a myriad of shapes, challenging players’ ability to adapt to a situation in constant flux. The players thus find themselves taking part in a form of social choreography, questioning whether it’s the field that is shaping the players’ actions—or if it’s they who are pushing the space’s boundaries.

SIDELINED uses the universal language of sport to challenge social norms | image by Temet.studio

DB: The exhibition aligns closely with this year’s Biennale theme. How does SIDELINED propose alternative forms of collective intelligence through its spatial and social provocations?

AP: Designed by Koos Breen and Jeannette Slütter, our sports bar merges high culture with pop culture. Here you can watch Gabriel Fontana’s new games, relax and read our sports new paper or play a game of fluid foosball where you make up your own rules. It is a dynamic space where traditional boundaries, hierarchies, and cultural norms can be challenged and redefined. The exhibition gives visitors the chance to critically examine how sport as a system embeds ideologies of power into its very design.

Drawing on Sara Ahmed’s theory of queer phenomenology, we have intentionally queered this space – transforming it into a sports bar that serves as a model for new modes of togetherness. This is a welcoming space where fluidity and experimentation can lead to a sense of empowerment for visitors. At our sports bar, sports is a tool for bridging diverse communities.

Koos Breen and Jeannette Slüttert transform the space | image by Temet.studio

DB: Sports usually reinforce binaries: winner/loser, us/them, male/female. How do your designs queer these binaries, and what kinds of new interactions have emerged as a result?

GF: Sport, as it is traditionally designed, often enforces rigid binaries that shape not only gameplay, but also how people relate to each other and to themselves. With my new team sports, I aim to queer those underlying structures by introducing Fluidity, ambiguity, and multiplicity into the rules, uniforms, and playing fields.

Rather than positioning queerness solely as an identity, I treat it as a method—one that challenges norms and creates space for different ways of being, relating, and cooperating. These games remove fixed roles and visible groupings, disrupting the standard logics of competition and hierarchy.

One of the most powerful outcomes has been witnessing how participants gradually shift from trying to “win” to trying to make sense of each other. The uncertainty embedded in the games invites curiosity, negotiation, and care. In Anonymous Allyship, for instance, players can’t rely on visual cues to determine alliances—they must pay attention, observe, and build trust in new ways. These micro-shifts in behavior begin to reshape how people understand collaboration, belonging, and power.

a hexagonal field of fluid interaction

DB: In working with collaborators across design, art, and theory, what unexpected insights or creative tensions surfaced, and how did they shape the final outcome?

AP: Collaboration is at the heart of my practice, and curating the Dutch Pavilion this year was a deeply rewarding experience precisely because of the diversity of voices involved. Working with practitioners across design, art, and theory brought an incredible richness to the process—what emerged felt much more than the sum of its parts.

Rather than encountering friction, we experienced a kind of creative generosity. Each discipline came with its own language and way of seeing the world, and those differences led to unexpected resonances. One of the most surprising insights was how aligned we all were in wanting to dissolve the usual boundaries—between theory and practice, aesthetics and politics, individual authorship and collective expression.

The result, I believe, is a kind of gesamtkunstwerk—a total work of art in which spatial design, conceptual frameworks, and artistic interventions are fully interwoven.

a sports bar filled with queer gym memorabilia | image by Temet.studio

DB: The exhibition positions sport as a kind of spatial system. How does your design approach treat sports fields, jerseys, and tools as architectural elements?

GF: Architecture has always been more than just the arrangement of walls, roofs, and spaces. At its best, it’s a social tool—one that can deeply influence how people live together, how they interact, and how communities are formed or fractured. The built environment can either promote connection or enforce separation, depending on the values and intentions embedded in its design.

Sport is a designed system that shapes both physical and social interactions. Stadiums, jerseys, equipment, and even the field of play operate within a designed framework that influences not only the game but also how individuals interact with one another. Sport’s infrastructure encodes power dynamics and societal norms into its spaces and objects, often reinforcing a competitive, capitalist, and heteronormative division of society.

By deconstructing the spaces, uniforms, and tools of sport, we can question the conservative values that these elements reproduce and challenge their role in shaping identity. Rather than seeing design as merely functional in sports, we will explore how it can be used to radically rethink the values and norms we want to promote on and off the field.

the pavilion becomes a speculative arena, where identity, belonging, and power dynamics are up for play

DB: When space itself becomes the primary medium, rather than objects, how does this shift your curatorial approach, and what does it demand of audiences?

AP: When space becomes the primary medium, rather than objects, it fundamentally reshapes the curatorial approach. It’s no longer about selecting and placing, but about composing an experience—one that unfolds over time and through movement and collectivity. In the Dutch Pavilion, this shift allowed us to think of the project as an overall experience, where architecture, play and fluidity are all interdependent elements of a single immersive whole.

It demands a different kind of attentiveness from the audience. Instead of consuming a narrative or viewing a series of works, visitors are invited to inhabit, to linger, and to engage with ambiguity. The space doesn’t “tell” in a didactic way; it evokes and invites.

What I found especially rewarding was how this approach opened up new forms of accessibility—not necessarily through simplification, but through sensorial richness. It created multiple points of entry, allowing different publics to find their own way in. That, to me, is the real potential of working with space as medium: it decentralizes authorship and encourages a more open, embodied form of encounter.

Fontana’s alternative games turn competition into collaboration | image by Temet.studio

DB: What was your process for designing rules that invite fluidity rather than rigidity? And how do you deal with participants who still default to conventional play styles?

GF: The design of fluid rules begins with questioning the assumptions that are usually built into games—clear teams, fixed objectives, and strict roles. I start by identifying those fixed structures and then experimenting with ways to loosen them. This often means introducing ambiguity into the game mechanics: shifting team compositions, concealed alliances, or responsive playing fields. These strategies make the game feel unfamiliar at first, which creates space for new behaviors to emerge.

Of course, some participants initially revert to what they know—seeking competition, dominance, or clarity. I see this not as a problem, but as part of the process. These moments of friction often become points of reflection. When players confront their own expectations and struggle with uncertainty, they begin to ask deeper questions: What does it mean to play fairly? To be an ally? To be a team? To win?

By building games that center exploration over achievement, and connection over conquest, I try to create environments where transformation can occur—not through instruction, but through experience.

the pavilion challenges how we socialize, cheer, and identify with others

DB: In curating a national pavilion with such an inclusive agenda, how do you balance institutional responsibilities with radical curatorial experimentation?

AP: Balancing institutional responsibilities with radical curatorial experimentation is a dynamic tension, but one that I see as productive rather than limiting. From the outset, we approached the Dutch Pavilion not as a platform to represent a singular national narrative, but as a space to question and expand what a ‘national’ pavilion can be—whose voices it includes, how it operates, and what kinds of futures it can imagine. An inclusive agenda requires rethinking the structures of authorship, access, and engagement—often in ways that challenge institutional norms. But rather than seeing those constraints as obstacles, we treated them as parameters to work with creatively.

with contributions from artists, the exhibition becomes a living archive of voices

DB: Your work turns games into tools for social transformation. What do you hope architects and designers take away from experiencing SIDELINED?

GF: Design for togetherness requires reckoning with inequality. It’s not just about creating spaces to be together—it’s about ensuring everyone feels safe, seen, and valued in those spaces. Queerness disrupts binaries—public/private, inside/outside, formal/informal—and opens up possibilities for new kinds of togetherness.

This exhibition relates not only to social innovation and design, but also the evolving challenges in the sports industry. Today, many sports brands are being pushed to rethink traditional narratives around competition, gender, inclusion, and emotional wellbeing. Consumers—especially younger generations—are demanding more inclusive, values-driven experiences. The Pavilion of the Netherlands addresses these shifts directly by redesigning the very structure of sport as well as the values and norms it promotes. This perspective offers a fresh angle, especially as brands look to innovate in ways that are socially impactful and culturally relevant.

Amanda Pinatih and Gabriel Fontana | image by Elizar Veerman

recordings from Venice’s Stadio Pier Luigi Penzo appear on the sceens | image by Giovanni Pellegrini

project info:

name: SIDELINED: A Space to Rethink Togetherness

curator: Amanda Pinatih | @amandapinatih

main exhibitor: Gabriel Fontana | @gabriel_fontana__

commissioner: Nieuwe Instituut | @nieuweinstituut

pavilion design: Koos Breen | @koosbreen, Jeannette Slütter | @jeannetteslutter

venue: Dutch Pavilion, Giardini, Venice

program: Venice Architecture Biennale | @labiennale

dates: May 10th — November 23rd, 2025

photographers: Temet.studio | @temet.studio, Cristiano Corte | @cricopix, Elizar Veerman | @elizarveerman, Giovanni Pellegrini, Giacomo Bianco | @g.i.a.c.o.m.o.b.i.a.n.c.o

The post an alternative sports bar within the dutch pavilion rethinks togetherness at venice biennale appeared first on designboom | architecture & design magazine.

What's Your Reaction?