‘we all can do more with less’: oshinowo studio brings lagos’ markets to the venice biennale

lagos markets land at the venice architecture biennale 2025

Lagos-based architecture practice Oshinowo Studio brings ‘Alternative Urbanism: self-organising markets of Lagos‘ to the 19th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, spotlighting three of the city’s most dynamic informal markets—Ladipo, Computer Village, and Katangua. Invited by curator Carlo Ratti to respond to his circular economy manifesto, the studio explores how these systems repurpose waste from the global north into valuable goods, offering a powerful model of embedded circularity. ‘These markets don’t work just as places of commerce and exchange,’ notes founder Tosin Oshinowo in an exclusive interview with designboom. ‘What is fascinating is the factory-like process that occurs when a source material is re-appropriated and adapted through different sectors in these markets,’ she tells us. Through immersive film, photography, data visualisations, and recycled denim maps crafted in Katangua, the exhibition reframes Lagos’s markets as complex infrastructures of ingenuity, shaped by scarcity and sustained by collective intelligence.

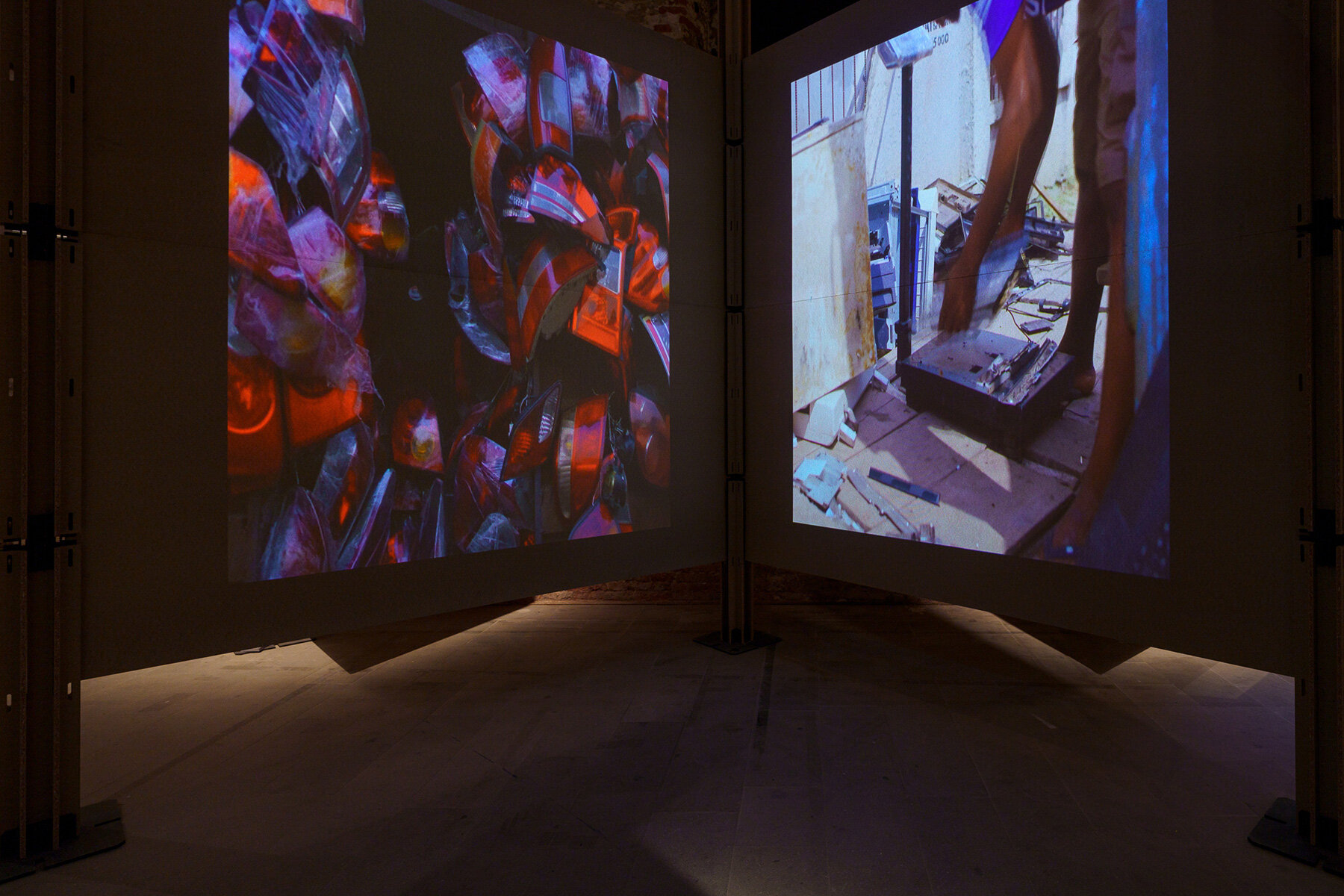

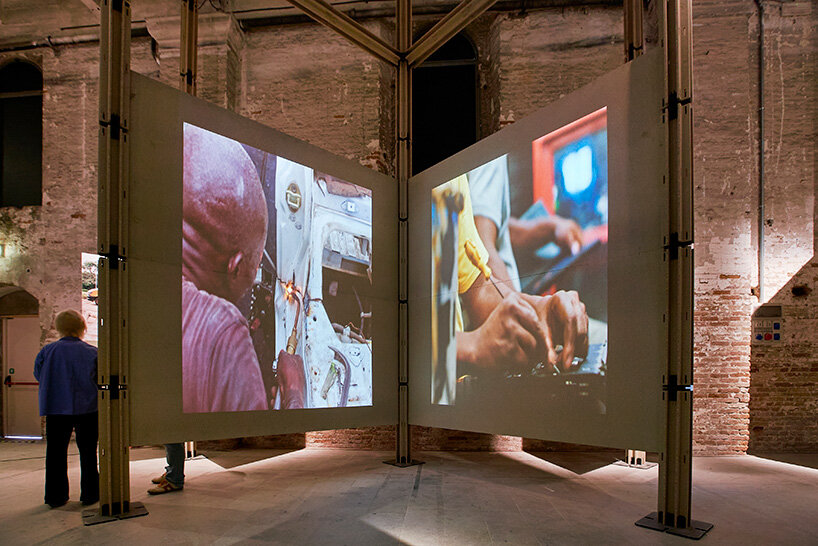

Rejecting voyeuristic representations of African spaces, the installation at the Arsenale avoids still images of deprivation and instead offers a technical view into the working mechanics of these markets. ‘It was important that the narrative be optimistic; after all, I live and work in Lagos,’ Oshinowo says. ‘I do not see what happens here as backwards or deprived; I see this as fascinating, innovative, and the other extreme of global capitalism,’ she adds. With her team’s mapping, video documentation, and textile production done within Katangua, the pavilion elevates local material knowledge to an international stage. In doing so, it delivers a clear message to Biennale visitors.‘The biggest lesson and shift in perspective I hope to share and inspire with this global audience is that we all can do more with less,’ Tosin Oshinowo suggests.

Alternative Urbanism: self-organising markets of Lagos at the Arsenale | image by Paul Raftery

Oshinowo Studio offers a blueprint for adaptive urban futures

Ladipo Market deals in second-hand car parts; Computer Village in used electronics; and Katangua in recycled fashion. While their contents differ, their shared value lies in how they extend the life of consumer goods through a communal network of reuse, repair, and resale. ‘These specialist markets emerge across the city in white and brown-fill sites, residential zones, and defunct industrial parks,’ Tosin Oshinowo shares with designboom. ‘Through a collective intelligence, the city operates at a sophisticated level outside of orthodox methodologies and functions at scale without the expected industrialized infrastructure.’ Her exhibition doesn’t romanticize the struggle but rather reframes Lagos’s informal urban systems as prototypes for sustainable cities—systems built from adaptation, making them increasingly relevant in a time of global resource scarcity.

As Oshinowo explains, these spaces represent ‘a glimpse into an urban condition without imperialism, colonialism, and modernism imposed on the continent.’ Far from being symbols of deprivation, the markets are framed as energetic ecosystems shaped by ‘bottom-up structures and soft-power systems.’ Located in areas ranging from residential zones to defunct industrial parks, each market illustrates the kind of grassroots adaptability often excluded from conventional urban planning. With Nigeria’s currency devalued by 700% since 2005 and most of the population living on under $2 a day, these markets respond with a resilience that blends necessity with aspiration. ‘The majority of Africa is urbanized but not industrialized,’ the Lagos-based architect explains. ‘This situation creates an urban condition that is alternative to conventional expectations of progress and development.’ Read on for our full interview with Tosin Oshinowo.

the studio explores how these systems repurpose waste | image by Paul Raftery

interview with Tosin Oshinowo

designboom (DB): Alternative Urbanism is a powerful title—how does it reflect your view of Lagos’s informal markets, and in what ways do they challenge conventional models of urban planning and sustainability?

Tosin Oshinowo (TO): The title is impactful; however, it simply states a reality that occurs as parallel development with the rest of the world. The majority of Africa is urbanized but not industrialized, and this situation creates an urban condition that is alternative to conventional expectations of progress and development. This research project uses the informal market as an entry point to understand this condition. Lagos is a heightened example of this condition because of its critical mass—the city has 0.3% of Nigeria’s surface area and 10% of its population, 26.4 million. With insufficient industrialized infrastructure, it is challenging to manage the city structurally. This density allows us to observe this condition in concentration. These markets happen when bottom-up structures and soft-power systems come to the foreground.

Rem Koolhaas’ research in the late 1990s and early 2000s observed that the urban condition in Lagos defied orthodox planning methodologies. Here, I suggest that instead of defying these methodologies, what we observe in the city condition reverts to an evolution from tradition. It could be considered a glimpse into an urban condition without imperialism, colonialism, and modernism imposed on the continent. The informal African market is the most unadulterated urban artifact of our city’s developmental framework. It is the fabric of the commons, a shared space everyone contributes to and shares in its benefits. The markets operate in a capitalist model and outside of it. The markets have evolved from pre-colonial times to their present state in the post-colonial African city. Holding more than just places of commerce and exchange, but also of divine importance. In Yorùbá culture from southwest Nigeria, the market holds divine significance in mythology as it is seen as the point of final departure for the soul from the earth (ilé) as it rightfully returns to the heavens (òrun).

recycled denim maps crafted in Katangua | image by Paul Raftery

DB: Carlo Ratti’s circular economy manifesto set the tone for this year’s Biennale. How did it resonate with your existing observations of Lagos, and what discoveries emerged from your research into these self-organizing markets?

TO: When I first read Carlo Ratti’s manifesto, I was excited that this research resonated with the theme and perfect timing. There is nothing more euphoric than realizing that you are part of a change movement. Circularity has been a long-standing practice in regions that deal with austerity. It is encouraging that there is a growing understanding globally that we all need to embody this methodology. When I started the research on the markets, it was initially out of an interest to understand how global south cities function at scale with inadequate infrastructure.

As I developed this narrative, I observed how sophisticated the system of markets and circularity is embedded into commerce and city life. I observed that due to Nigeria’s challenged economic condition and the reality of desires to live in modernity, capital-intensive consumer products are outside of the immediate reach of the average Nigerian consumer, with the Nigerian Naira devalued by 700% since 2005. These markets don’t work just as places of commerce and exchange. Several specialist markets sell second-hand products considered redundant from the global north. What is fascinating is the factory-like process that occurs when a source material is re-appropriated and adapted through different sectors in these markets. These markets effectively take waste from the global north and extend product life while producing less carbon.

the exhibition reframes Lagos’s markets as complex infrastructures of ingenuity | image by Andrea Avezzù

DB: Ladipo, Computer Village, and Katangua each represent a different kind of circular ingenuity. Why these three, and what do they collectively reveal about resilience and resourcefulness in urban Nigeria?

TO: So far, the research has documented 80+ specialist markets, as the convergence of like-for-like across the city’s urban fabric has been fascinating. I selected these three markets for the exhibition because their content deals with circularity. Like all markets, they deal with consumer goods, but these three represent staples of modernity. And the opportunity for people in these regions to afford capital-intensive consumer goods like cars, electronics, and clothes. Where does the hyperconsumerist global north dispose of its waste? Today, two-thirds of Nigerians live on less than $2 a day. These conditions create the fertile ground to harbor this kind of circularity not seen before structural adjustment programs imposed on the global south from the mid-1980s and early 1990s.

the installation offers a technical view into the working mechanics of these markets | image by Andrea Avezzù

DB: Your pavilion merges data, video, and recycled textiles to evoke the atmosphere of the markets. How did you navigate the challenge of capturing their energy and complexity within the formal setting of the Arsenale?

TO: It was challenging, particularly because I was mindful not to share this as a narrative of deprivation, which can easily come across by using still images from Africa. It was important that the narrative be optimistic; after all, I live and work in Lagos. I do not see what happens here as backwards or deprived; I see this as fascinating, innovative, and the other extreme of global capitalism.

The essence of the immersive film of the market captured a narrative of intense activity and optimism. It was a great privilege for the team to have access to film and photograph these spaces, and we do not take for granted the immense trust we have been given. It was also important that this did not become just an immersive film; we wanted to ensure that we showed a technical prowess to document the urban condition of these markets, which we showed through a series of mappings taken of each market and its surrounding urban fabric. The medium we used to show these was heat-transfer graphics placed in recycled denim patchwork, all produced in the Katangua market. Coupled with pause moments captured through photography, it created a visual language that was intriguing and enigmatic in its context.

immersive film, photography and data visualisations shape the exhibition | image by Paul Raftery

DB: The notion of ‘communal intelligence’ underpins your curatorial narrative. How do these markets embody that idea, and what lessons might formal design systems draw from it?

TO: The specialist markets in Lagos are informal; the state does not plan them, and they have emerged due to specific conducive political, social, and economic conditions. These markets as individual nodes have clear governing and management structures. Still, observing from the macro level, it’s fascinating to see that through a collective intelligence, the city operates at a sophisticated level outside of orthodox methodologies and functions at scale without the expected industrialized infrastructure. It is outside of conventional ways of thinking about the modern city, which tends to be the top-down result of the collective few. These specialist markets emerge across the city in white and brown-fill sites, residential zones, and defunct industrial parks. These markets resonate with the theme of communal intelligence, highlighting the system that speaks to an alternative urbanism, which contributes sparingly to our global carbon challenge in their operation and an optimistic conversation on circularity.

Katangua Market overview | image by Andrew Esiebo

DB: With a global audience in Venice, what shifts in perception about African cities—especially Lagos—do you hope this exhibition might provoke or inspire?

TO: The world can learn a lot from African cities. This region, which is the least industrialized yet urbanized, contributes the least to global carbon emissions while suffering some of the most severe damage. The biggest lesson and shift in perspective I hope to share and inspire with this global audience is that we all can do more with less.

market stall at Computer Village | image by Nengi Nelson

project info:

name: Alternative Urbanism: self-organising markets of Lagos

architect – curator: Lagos-based | @oshinowo.studio

founder & lead curator: Tosin Oshinowo | @tosin.oshinowo

location: Arsenale, Venice, Italy

program: Venice Architecture Biennale | @labiennale

dates: May 10th — November 23rd, 2025

photographers: Paul Raftery | @paulrafterystudio, Andrea Avezzù | @ave_zz, Andrew Esiebo | @andrewesiebo, Nengi Nelson | @nenginelson1, Taran Wilkhu | @taranwilkhu, Amanda Iheme | @amandaiheme, Olarenwaju Ali | @olanrewaju_v

The post ‘we all can do more with less’: oshinowo studio brings lagos’ markets to the venice biennale appeared first on designboom | architecture & design magazine.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0