"China is making a clear statement about its status in its architectural expression"

A distinctive approach to designing and portraying architecture has emerged in China that has as much to do with politics as design, writes Austin Williams. Type "China's Contemporary Architecture" into Google Images and you will be confronted by a vast array of weird and wonderful buildings. Many are iconic, designed by foreign and domestic architects, The post "China is making a clear statement about its status in its architectural expression" appeared first on Dezeen.

A distinctive approach to designing and portraying architecture has emerged in China that has as much to do with politics as design, writes Austin Williams.

Type "China's Contemporary Architecture" into Google Images and you will be confronted by a vast array of weird and wonderful buildings. Many are iconic, designed by foreign and domestic architects, from Patrik Schumacher to Tadao Ando, from MAD to TAO. Love them or hate them, each one seems to have a novelty, an inventiveness, that is peculiarly identifiable to China.

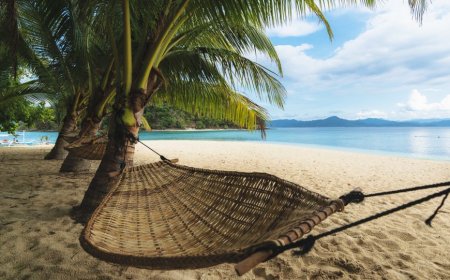

Much like Cecil B DeMille's epic US movies from 100 years ago, Chinese architecture often offers aspirational, feel-good narratives that float above the grim reality of everyday life. The work often implies a transcendence. The dreariness of architecture's urban context is often marginalised in architectural photography, for example, where the resultant images have a dreamlike quality: white concrete and gentle illumination in front of a mountain or on the banks of a lake.

Ten years ago, it seemed that experimentation was over

For China's architecture firms it has been a successful approach. Even though most rarely practice abroad, they are feted in the global design press.

But this is about more than just design. The emergence of this distinctly Chinese trend is firmly based in politics – and it tells an interesting story about how China's elite views their country in the current world.

Around 10 years ago, it seemed that experimentation was over. Chinese president Xi Jinping announced that there was to be "no more weird architecture". By then, China had become something of a playground for Western architects, some of whom found that they were unable to get commissions post-recession in the West, and therefore turned to China to vent their creative frustrations.

Fundamentally, the criticism of "weird architecture" was a governmental mandate intended to serve two purposes.

On one hand, it was an attempt to discipline the spendthrift tendencies of local party apparatchiks who had been commissioning lavish architecture to further their careers; and on the other, it was the start of president Xi's demand that the profession ought to stop relying on Western influence and be more proactive in reinforcing Chinese cultural identity. Specifically criticising OMA's CCTV HQ, the Central Committee of the Communist Party called for an end to "oversized and xenocentric" urbanism.

As we have seen, over the intervening period this hasn't occurred in the exclusionary manner that many had predicted, and many Western practices still remain active in the country today.

Architects are obliged to respond to Central Party diktats

But the cultural framing of contemporary architecture commissions in China did change in a more nationalistic direction. This has not only found expression in the way that buildings are designed, but also in the way that they are visually represented: drawn, modelled, framed and photographed.

Chinese architectural renderings and artists' impressions are regularly produced with the intention of over-emphasising the building in isolation. In fact, it's a common problem for architecture students the world over, but in China it has become an art form, where the image of the commissioned building must be spotlighted to the detriment of all others.

Iconic buildings are constantly conveyed as architectural islands floating in a sea of vegetation, regardless of whether it is actually being designed for an extremely built-up or industrialised area. This is partly because clients want to promote their specific building in a very competitive market, and also due to the fact that China's urbanism has been created so rapidly, that "urban context" has often become an irrelevant luxury.

But there are other aspects to the way that Chinese architecture is presented these days that are mostly premised on China's political ambitions rather than anything integral to architecture, per se. Architects are obliged to respond to Central Party diktats currently highlighting Chinese values, culture and aesthetics.

The Rural Revitalisation programme, for instance, has pushed many young architects away from first- and second-tier urban centres and into small rural villages to help alleviate poverty and environmental degradation; an admirable aim. Actually, the strategic rationale for this initiative is to restrict migration – give the peasantry more things and they'll not leave and overpopulate the cities.

Unsurprisingly, many of these commissions are white elephants, where excitable architects have been allowed to design huge, parametric shapes in agricultural settings on the pretext of employment, tourism, jobs and money that often don't materialise. As one researcher has put it, "the pressing needs of local populations… are frequently subordinated to heritage preservation and the ambition of planners." All too many of these schemes are the Potemkin facades that we see in glossy magazines.

Ancient concepts are being used – legitimately or pragmatically – to justify even the most modern of buildings

Secondly, the development of an Asian oeuvre – as opposed to a purely Chinese aesthetic – has become important to party policy-makers. At the moment, China is developing influence in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and, having studied the way that anti-colonial activists have condemned Western imperialism, doesn't want to be seen to be imposing itself on less developed countries, even if it is. By desperately holding on to its "non-interference in the internal affairs of another country" pledge, it prefers to build soft power links with the region.

Aesthetically, some of China's contemporary architectural ideas reflect the alluring modern designs from Japan and South Korea. With China's backing, these are then creatively absorbed into a new regional form of expression. Growing geopolitical tensions may alter this relationship in the future, but it is a work in progress for China and an expression of its diplomatic multipolar ambitions.

Finally, it is clear that China has a wide selection of world-class, home-grown, internationally trained architects who can draw on a range of traditions and styles. However, the country's recent shift towards nationalism and self-sufficiency is putting pressure on architects to sing from the party's hymn sheet, cynically or otherwise.

From Ma Yansong's Chaoyang Park Plaza, to Wang Shu's Ningbo Tengtou Pavilion; from Neri & Hu's Chuan Malt Whisky Distillery to Haoyuan Group's Library in the Valley, many Chinese architects are claiming to base their designs on the "shan-shui" aesthetic – the old ink or watercolourist images of mountains and water that represents Taoist notions of harmony. These ancient concepts are being used – legitimately or pragmatically – to justify even the most modern of buildings.

It is worth noting that during China's emergence from imperialism in the 1920s, many Chinese artists and architects trained in the West and set up practices in China on their return. Instead of integrating the two styles, they produced Chinese-style architecture one day, and Western-style the next.

The Chinese national, patriotic spirit seems to have won out

In this way, the foundations of a new China were torn between modernist architecture that expressed its engagement with the wider world, versus a more introspective, nationalistic and nostalgic vision of what China should be. The architects of the day, 100 years ago, toyed with both. One writer describes how, in the late 1920s, architect Liu Jipiao tried to simultaneously "address the 'past', invent 'tradition', and create an 'artistic modernity'".

Back then, it was a battle of ideas to create the new China. Today, that intellectual tussle is not so prevalent, because the Chinese national, patriotic spirit seems to have won out. Whether you agree with it or not, China is making a clear statement about its status, in its influential, architectural expression.

Austin Williams is a director of the Future Cities project, and course leader in professional practice at Kingston School of Art. As a critic he specialises in Chinese architecture, having authored the books China's Urban Revolution and New Chinese Architecture.

The photo, showing The Seaside Chapel of Jinting Bay by O-office Architects, is by Wu Siming.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.

The post "China is making a clear statement about its status in its architectural expression" appeared first on Dezeen.

What's Your Reaction?