"Patrik Schumacher presents a stark and exclusionary vision of the state of architecture"

Patrik Schumacher's argument about architecture's problems ignores reality, writes MASS Design Group's Alan Ricks.

In his recent essay The End of Architecture, Patrik Schumacher argues that architects must reject pluralism, disengage from social and environmental concerns and focus on formal and technological innovation. He presents a stark and exclusionary vision of the discipline's state.

I don't know him, and I admire much of the work created by Zaha Hadid Architects.

However, I do not agree with him. Architecture does not have to choose between innovation or responding to social and environmental needs, form or service, theory-driven work, or real-world concerns; these are not opposing forces and are false choices.

History has never seen a universal style adopted, thank goodness

Schumacher claims that architectural progress requires us to coalesce around a singular paradigm and that fragmentation is a weakness. He goes further to say that this coalescence has happened at other points in time and that divergence is the anomaly.

This ignores the reality that history has never seen a universal style adopted, thank goodness. While specific movements have shaped discourse and practice in particular geographies and intellectual circles, they have always coexisted with diverse, contextually rooted innovations that happen elsewhere.

The idea of singular, dominant paradigms is a retrospective construct of those who have historically controlled architectural discourse. For every prevailing trend in the Eurocentric canon, innovative, context-driven developments have occurred across Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Latin America.

Architecture has always been a diverse and adaptive field, evolving through dialogue, debate and the influence of regional, cultural and environmental conditions. Pluralism drives innovation by enabling diverse approaches to develop and challenge each other.

Social, political and ecological factors do not conflict with formal and technological innovation; quite the opposite. By working in the realm of social impact, we open the opportunity for new formal, material and process innovations.

Celebrating the creativity in the spaces we shape and create can and must coexist with the effort to solve the most pressing challenges of our time – climate adaptation, migration and building communities where people can have a sense of belonging and the possibility of shared prosperity. Here, we need the best and most creative minds and theoretical rigor just as much as we need to advance formal ingenuity. To relinquish this effort to other fields would be to undermine the importance of design's role in shaping a thriving and abundant future.

Schumacher's argument denies architecture's fundamental reality

Walking through Lesley Lokko's last Venice Architecutre Biennale, I had an altogether different experience than Schumacher. I was inspired by not only the range and depth of the work but also the fact that the ideas, experiments and examples of built projects that I was most enamored of were often from designers I was unfamiliar with. The biennale represented the best of what a speculative endeavor can be, creating the opportunity to push boundaries, challenge preconceptions, spark debate and, perhaps most critically, make space for new voices to emerge.

We cannot be limited to formal novelty as a measure of architectural progress. Work by Zaha Hadid Architects and others elicits a sense of wonder and invites us to reconsider what we might not have thought possible. This is immensely valuable and one of the many powerful impacts of architecture.

At the same time, architectural innovation extends far beyond form-making to material science, construction methodologies, sustainability strategies, participatory design processes, theoretical positions and educational pedagogies.

Great work challenges the status quo – formally, ethically, inclusively, economically and socially. What we value should not be solely determined by disruptions and innovations in what can be done but by taking a holistic view of what should be done. Novelty can be wasteful, environmentally harmful and disconnected from human needs. It can also be transformational, awe-inducing and galvanizing.

Schumacher's argument denies architecture's fundamental reality: the built environment is always political, always social, always shaping and shaped by context. To claim otherwise is not only unrealistic – it is untenable.

Our choices about materials, clients, land use and development directly and indirectly impact communities, economies and ecosystems. Each choice we make is an opportunity to advance progress toward a future where people and the planet flourish. We affect biodiversity, air and water quality and carbon footprints; we shape spaces that influence economic mobility, safety and accessibility. Ignoring this agency diminishes architecture's power.

The real danger is not pluralism but isolation, and a refusal to engage with the world's complexities

The responsibility of architects is not just to build boldly or radically but to build wisely and with an awareness of the human and ecological systems we operate within and endeavor to serve.

He is right that rhetoric is insufficient. Simply naming these things does not absolve us of the responsibility to deliver solutions. Protest and provocation are useful and necessary to challenge the status quo and encourage us to push further, but we need more built examples and evidence to guide us in continuing to disrupt and innovate with new, better and novel solutions.

Architecture's future lies in complexity, not assimilation and exclusion. It will be found in our ability to integrate multiple perspectives and constituents and to effectively work in the incredibly complex systems and challenges we face as a collective society.

Parametricism has a place in this conversation, just as the work of MASS and others does. Debate should be rigorous but inclusive. We must embrace difference and resist the impulse to narrow the possibilities of what might be transformational.

Rather than framing a discourse about relevance, goodness and intellectual relevance, we should ask: how can we advance architecture in a way that is both aesthetically stimulating and also just? How can we create a discipline that remains intellectually rigorous while also relatable and engaged in the world outside the discipline? How can we create a culture where critique is constructive, rather than exclusionary?

The real danger is not pluralism but isolation, and a refusal to engage with the world's complexities. The way forward is not to retreat into an insular discourse that is only important to those in the discipline, but to embrace the opportunity to continue expanding architecture's relevance outside of it.

Alan Ricks is a co-founder and principal of MASS Design Group.

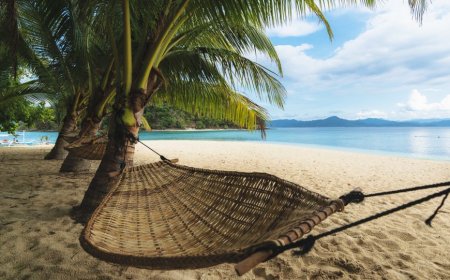

The photo shows MASS Design Group's Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture campus, which won sustainable project of the year at Dezeen Awards 2024.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.

The post "Patrik Schumacher presents a stark and exclusionary vision of the state of architecture" appeared first on Dezeen.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0